Getting to ethical grips with AI

Our ethics lessons are an opportunity for students to engage in meaningful discussions of real-life issues. These discussions are not just academic – they’re about equipping young minds with skills in critical thinking, ethical reasoning and respectful discussion that will help them navigate the complexities of the world they’re growing up into.

Practical ethics isn’t a static subject. Since our curriculum was first developed, we’ve seen some pretty significant changes in the sorts of technologies students engage with on a day-to-day basis. Technologies that bring with them a whole host of new (and sometimes old) ethical dilemmas.

Is it okay to use artificial intelligence to help with schoolwork?

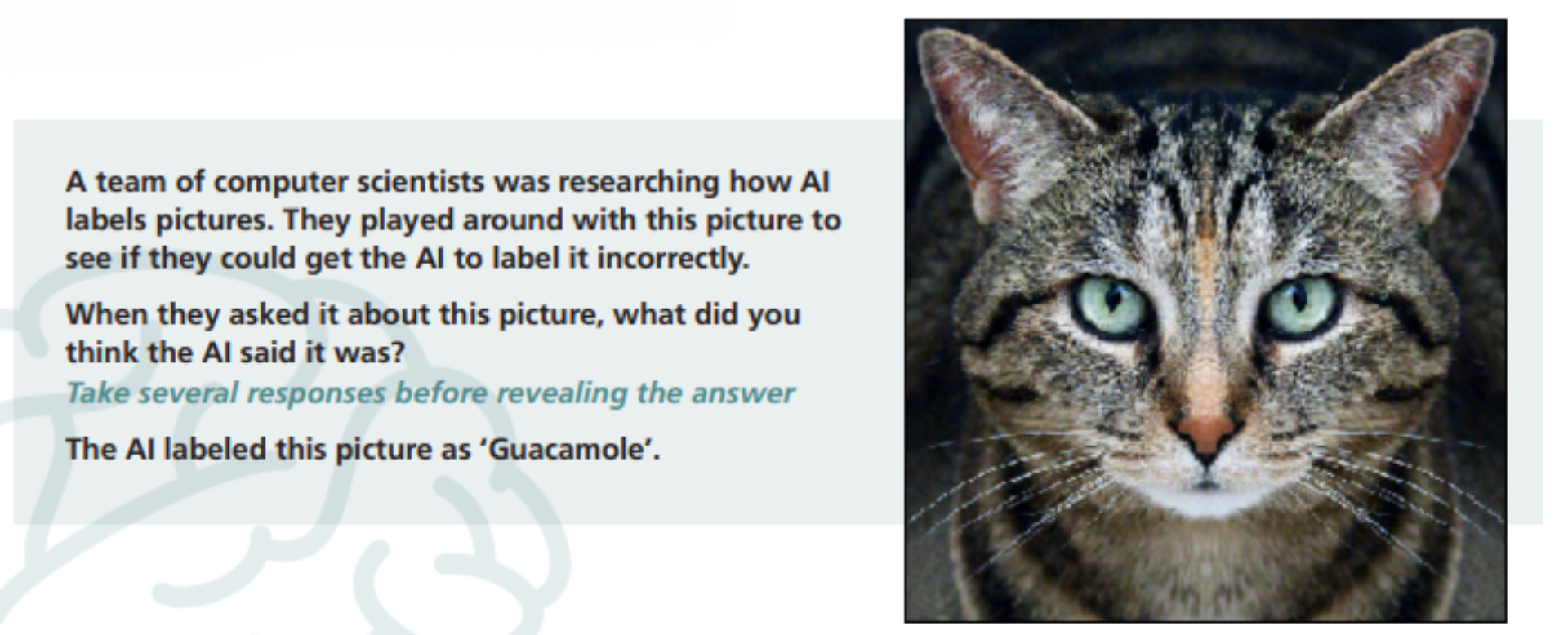

As artificial intelligence (AI) technologies like chatbots, search engines and personalised recommendations become ever-present in students’ lives, it’s important for them to reflect on how they engage with such technologies. So we’ve developed an exciting new topic on AI for Stage 3 (Years 5-6). Some of the big questions students consider in this topic include: How is AI different from and similar to human intelligence? Is it okay to use artificial intelligence to help with schoolwork? To what extent can we trust AI and how do we know when not to trust it? Can we be friends with a chatbot? Is it bad to be cruel to artificial intelligence?

This new addition to our curriculum is not just about keeping pace with technological trends. It’s about preparing students for a future where they can confidently and ethically navigate the digital landscape. By fostering a deep, nuanced understanding of these issues, we’re helping shape a generation of informed, ethical digital citizens.